BY HUIZHONG WU

My best friend in middle school had dark blonde hair, blue eyes and a cocker spaniel named Hershey. Her house in the middle of the city had a small patio area covered in plants and a sliding screen door. She had cake mix and muffin pans and a bar counter in her kitchen where we would spend the hours after school.

I had a train pass that would carry me from the center of the city back home to the flat suburbs where old Catholic immigrants from Ireland had settled several decades ago, mismatched dinnerware which my mother had picked up at various sales at as many stores, and this greyish white scratchy carpet that always left my skin red. I knew how to navigate the public transportation system by myself to most corners of the city, but had never had an easy conversation with an adult about how my day was at school in English, the language I was more comfortable in. At her house, I learned to chat with her mother, who ran two miles a day and was a great baker.

Through hours-long phone calls on weeknights, to sleepovers and after-school homework sessions, I could for a few hours live the life that I wanted. What that life was, I thought I knew. I found that her life was more real, more like the life of someone who read American Girl books or mirrored Rory Gilmore’s storybook New England town life; Moms who made brownies and comfy couches with throw blankets and a cocker spaniel running around begging for scraps. Over the years, I found that it was a world I could take cover in. With my friends’ parents, I enjoyed playing the role of the responsible friend, the one who got A’s and helped clean up after dinner and who would never go with their daughter to some party and drink underaged. I spent days at their beautiful houses with hardwood floors, and walls decorated with paintings by artist friends and wardrobes which towered. These houses were rare in my neighborhood. And with their parents’ approval, I could feel my own genealogy taking shape, a curated genealogy, a self-made family history in a long history of pull-yourself-up-by-your-bootstraps Americanism. I was not like those unfortunate victims of Youtube pranksters whose broken English, which sounded like my parents, was turned into a joke for millions of viewers. I had nothing to do with them.

Still the creamy pleasure of escaping into this world inevitably soured, because I always had to go home. One day, in one of our countless fights, my mother said to me in Chinese, “why don’t you go live with them? You obviously don’t want to come home,” and I felt the immeasurable distance between my idealized life and my own.

Most of us shed these anxieties upon leaving adolescence. I thought I did too, but they reared their head again when I moved to India and made new friends. One of these friends who I became close with was someone who had thick, Pantene shampoo-ad hair and bookshelves filled with books that her father had read. She had a mother that could converse with people from all walks of life in a fluent, Indian-accented English. I had an air pollution mask, a sweaty face and dust-covered feet because I always wore sandals.

This must have been what Anne felt when she met Diana for the first time in the novel “Anne of Green Gables” – overwhelmed by her stylish frocks and black curly hair, with Anne every inch the orphan girl with scarecrow limbs in the ugly shapeless dress that Maria had kind-heartedly made for her. But Diana was a real girl, and my friend was real too – in all the imperfect ways that human beings are real. Yet as our friendship developed, I felt drawn again into the past. This time, I donned the guise of an educated American guest, getting myself invited to home-cooked South Indian vegetarian meals and conversations about development projects over a glass of red wine. Again, I charted a different genealogy in my head, but didn’t say anything out loud. I didn’t want to admit it to myself. I couldn’t.

In a foreign country, far away from any family, I learned how to be with myself. And that self, ironically enough, craved the ties of family that I had spent more than a decade trying to get rid of. Through time and distance, I had come to realize a paradox: which was that I could be both exactly who I wanted to be and that I can never escape who I am.

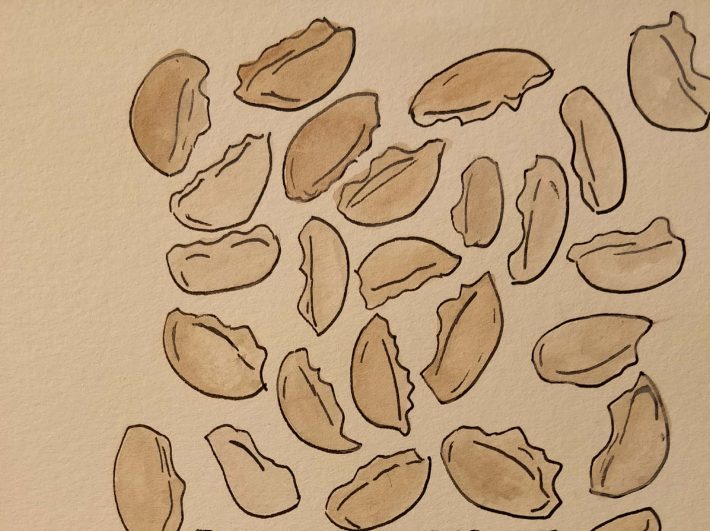

Many immigrant children go to their home countries to learn their origin myths. I am not one of those, and yet, a few years later, I found myself buying a one-way ticket for China. Not long after, I was sitting down at a kitchen table with my father who was visiting Beijing. It was the first time we had seen each other in six months. He and my aunt were folding dumplings; my three-year old cousin running around, babbling. We talked about her starting kindergarten and my father’s plans for the day of running errands around town. My aunt asked me, “Do you know how to fold these?” I responded, in an offended tone of voice, “of course!” though perhaps not as well she and my father. I washed my hands and then started filling a wrapper with the filling. Then I dipped my fingers in the bowl of water to draw a line around the rim of the dumpling skin, hands dry from the flour dust, wet from the water and sticky from the filling. I felt the distances that I’ve traveled and that I’ve created, shrink to something small and manageable, like the small round dumpling wrapper in my hand.

About the author

Huizhong Wu is a journalist who has reported from the United States, India and now China. She has written for Al Jazeera, CNN and the Guardian, among others.

Visit her website and follow her on Twitter @huizhong_wu

About the artist

Shirley Yan is a public health designer and a master’s candidate at Johns Hopkins University who is currently residing in Guyana. Follow her on instagram @yantaro33