BY ANDRÉ-ANNE CÔTÉ

“Ayi, why did you start working at the orphanage?” I asked.

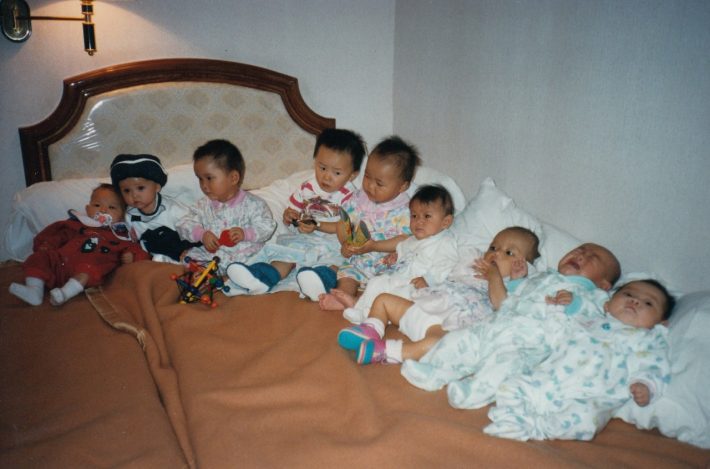

“Because I had to. Orders were coming from the top. Of course, I wouldn’t have chosen this job,” the orphanage worker replied. “Every week, around 200 children were left at the door at the institute. The One-Child era was terrible!”

The One-Child policy was a state initiative introduced in China in the 1980s that prevented most families from being able to have more than one child. Recently relaxed, the policy was enacted to control population growth, which was seen as too rapid at the time.

I am a Chinese adoptee who was abandoned in 1995 by my birth family in Nancheng, a city in China’s Jiangxi Province. I was sent to a local orphanage, where I was adopted by my family and brought to Quebec. Many families who gave up their children during that period were forced to do so, and came from rural backgrounds. The birth rate before the 1980s was high, and there are many testimonies detailing how many people actually desired large families at the time. Female children were also disproportionately abandoned, since cultural preferences prioritised sons over daughters. Two years ago, I returned to China and attempted—unsuccessfully—to find my birth family. Since then, I’ve been raising awareness on the plight of Chinese adoptees from abroad.

Over the past two decades, Chinese adoptees like me from all over the world have returned to the motherland in search of answers. The adoptees who return are faced with a China that is rapidly changing. Although China’s growth encourages international exchanges, the government is still ignoring waves of returnees, and does little to help those searching for their birth parents.

My interactions with the personnel of the Nanchang orphanage in 2018 left me skeptical about their willingness to help adoptees. My trip started with a visit to a small exhibition at their entrance, which featured a quote that described Chinese President Xi Jinping as the father of all orphans of the nation. It also offered bits of historical background, such as how the orphanage dates back to the year 1180 in the Song Dynasty, but did little to address the plight of adoptees.

The tour continued, but the interactions seemed forced. After complimenting my language skills in Mandarin, they switched to the Nanchang dialect, which made it more difficult for me to understand them. From what I did catch, the orphanage officials seemed to regard any encounters with villagers (many that gave up their children during the One-Child Policy era were from disadvantaged backgrounds) would hurt their pride and make them “lose face,” and were inappropriate for foreigners. I was also warned that they must verify any requests regarding potential birth parents, due to the frequency of scams in China. It seemed like they were trying to prevent me from interacting with any women who could potentially be my biological mother.

The visit ended with an awkward ritual: they added my handprint to a wall covered with prints from other adoptees’ who had returned. I was expecting a little more authenticity, but everything had been planned and polished to ensure the orphanage was in order, likely to prevent scandals like the one that occurred after the release of the 1995 “Dying Rooms” documentary. The documentary highlighted the maltreatment of children in orphanages.

After the visit, I finished writing my master’s thesis at Peking University on Chinese adoptees returning to the mainland, before returning to Quebec. I found three main motivations for their return: tourism, the desire to learn about their roots, and the desire to pursue professional and academic opportunities. Now, I’m an active participant in various international adoptees networks.

Through these channels, I’ve met members of the first generation of adoptees (who were adopted just after the Korean War) who helped establish organisations like the Global Overseas Adoptees’ Link and KoRoot, both established by and for adoptees. I’ve also built transnational ties with younger generations of Chinese adoptees from Canada, the United States, the United Kingdom, Spain and the Netherlands. All are eager to learn more about their origins. Last year, I was invited to present my research findings to the delegation of the China Center for Children’s Welfare and Adoption (CCCWA). I’ve also been in touch with other individuals involved in adoption agencies in Canada. One Chinese translator who worked in an adoption agency in the 1990s even invited me to dinner to apologize for their role in the traumatic consequences of the One-Child Policy, and for profiting off of what was essentially institutionalised human trafficking.

Many of us believe that the implementation of post-adoption services would be a good step towards healing the wounds left by the One-Child Policy. Such services include language programs, root-seeking trips and tools enabling access to family archives for adoptees who seek reunification. However, the biggest challenge in obtaining post-adoption services is the Chinese government’s lack of willingness to help us search for our birth parents. Today, the CCCWA’s primary goal is to ensure the continuation of adoption to Western countries, rather than to support reunification efforts.

The CCCWA delegation showed a high level of interest in developing a language and culture program. But in terms of looking for our birth parents, the representatives were unsure about where to begin, and how to implement an official procedure for testing the DNA of thousands of adoptees. At the moment, the delegation could only help us through using their guanxi (contacts) with officials or journalists to reunite families. The restrictions on civil society in China also make it difficult for us to ask NGOs and other institutions for assistance.

So why is China still so reluctant to help us find our birth parents? After watching the documentary “One Child Nation,” I believe that this is because the government is concerned that doing so would cause more people to discover the truth about the forced sterilizations, abortions and child trafficking that marked the implementation of Chinese family planning policies. Directors Wang Nanfu Wang and Zhang Jialing likely never intended to discover such atrocities, yet their documentary unexpectedly revealed the realities of child trafficking and adoption-derived networks, in addition to highlighting the abuse of women’s rights and bodily autonomy. Yet despite exploring such critical issues, the documentary did not include the voices of any adoptees.

Now, there is growing interest in our stories. The Museum of Chinese in the US held an event in November inviting American adoptees from China to speak about their experiences in the context of the One-Child Policy. At this moment, China has a unique chance to recognise its mistakes and heal the wounds left by this policy. The government could use this juncture to promote the reunion of birth parents and adoptees, after more than 20 years of separation. The Chinese government likely never expected to see so many adoptees return, but our desire for reunification and answers regarding our identities remain strong. It is up to the state to decide whether they want to accompany us in our process. Instead of ignoring this wave of returnees, the government should embrace us—and mark this decade with new relationships and solidarities.

About the author

André-Anne Côté is a culturally French-Canadian Chinese adoptee who was raised in Quebec, Canada. In addition to a B.S. in Anthropology from Laval University, she holds a Master’s in International Relations from Peking University. Her thesis examines the return of Sino-Canadian adoptees to their homeland. Her writing has been published in NüStories, Inkstone and other more. Find her on Twitter and Instagram.

About the editors

Annabelle Jarrett is completing a MSc in International Affairs in London. Having previously lived, studied and worked in Beijing, she is interested in the intersection of women’s issues and contemporary China. She enjoys writing on these topics, as well as tracking broader sociopolitical currents. Follow her on Instagram.

Jessie Lau is a journalist, researcher and artist from Hong Kong covering identity, human rights and politics, with a focus on China and other parts of Asia. Her work has been published by Foreign Policy, The Nation and The Economist, among others. She serves as Board Member and Online Editor-in-Chief at NüVoices, and was formerly a news reporter with the South China Morning Post. Website: www.laujessie.com. Twitter: @_laujessie