BY DAISY SINGH-GREAVES, SILVIA FROSINA AND CINDY GAO

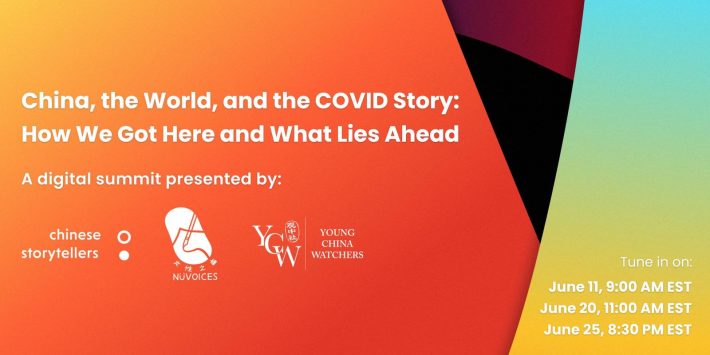

In response to the rising tensions in China and the world following the viral outbreak of COVID-19, NüVoices partnered with Chinese Storytellers and Young China Watchers this month to host a digital summit “China, the World, and the COVID Story: How We Got Here and What Lies Ahead.” The summit consisted of three panels featuring diverse journalists, experts and diaspora writers reflecting on the pandemic’s geopolitical implications. Hundreds tuned in to the discussions from across the world, making the inaugural collaboration a sold-out success.

- NüVoices is an international editorial collective gathering veteran and emerging writers, journalists, translators and artists to celebrate and support the diverse creative work of self-identified women working on the subject of China (broadly defined).

- Chinese Storytellers is a community serving and elevating Chinese professionals in the global media industry. You can follow us on Twitter @CNStorytellers.

- Young China Watchers is a global organization made up of ten chapters spanning China, Southeast Asia, Europe, the United Kingdom and the United States. Through in-person and virtual events among each chapter, as well as globally accessible media content including podcasts, interviews and editorials, YCW provides a chance for engaged individuals to interact and discuss the most pressing issues emerging from China today.

Cultural Timelines of the COVID-19 Pandemic

The first webinar opened up the discussion on how the virus intersects with geopolitics, race and scientific collaboration. The panel was moderated by Rui Zhong, Program Assistant for the Kissinger Institute on China and the United States at the Wilson Center. It featured Diana Yeh, Senior Lecturer at City, University of London, Sophia Yan, the Telegraph’s China Correspondent and Cornell University Postdoctoral Researcher Yangyang Cheng. The panel briefly came under a Zoombombing attack by far-right extremists who sought to disrupt the event, but coordinators Cindy Gao and moderator Zhong skilfully managed the situation and quickly expelled the users, paving the way for a fascinating discussion.

Yeh recalled how initially European governments “othered” the threat of the coronavirus, meanwhile many diaspora communities saw family members and livelihoods affected in real time. The UK’s already hostile Brexit climate, amalgamated with this narrative, led to an unprecedented rise of anti-Asian violence – further exacerbated by the disproportionate number of minority infections and deaths. Yan added that as countries worried about their reliance on trade with China, the geopolitical discourse tended to gloss over the people underneath. As many East and South East Asians have been personally impacted as collateral, governments need to urgently reassess how discourse continues moving forward.

Cheng analyzed the way scientific knowledge has been received and shared. The most influential political entities in this process – the US and Chinese governments and the WHO – have rapidly lost credibility when we need collaboration more than ever. Along with the media badly portraying scientific consensus, the public has been left with a mirage of often contradictory information. Cheng outlined the dangers of scientific competition and loyalty to national interests in this context. As something unconfined by borders, the pandemic has revealed the limitations of “nations” being organizing units for strategy and response, she said. Cheng added that there’s been too much focus on the location of scientific research, rather than its quality or motive. “What future might lie on the other side takes our collective imagination and effort,” Cheng said.

On the issue of collective social action, Yeh outlined that in the UK, East Asians have not historically organized against racism. Some generations were curtailed to “model minority” politics, feeling safer not calling out state racism, or fearing that reporting racial attacks to the police may affect business. Deeply troubling for those supporting the Black Lives Matter movement has been blatant anti-blackness in Asian communities, she noted. However, Yeh indicated that East and South East Asians have come together for the first time on mass, citing initiatives such as Daikon and Moongate Productions. Cheng echoed her sentiments, saying that the sudden switch from being perceived as the “model minority” to “pathogen carriers” made Asians’ racialized existence more acute, causing a collective awakening and solidarity.

From within China, Yan observed the measurable potential of propaganda. The government successfully redirected public anger against their handling of the pandemic into a broader anti-foreign sentiment, she said, citing how Beijing has used the situation in Hong Kong, shootings and the BLM protests to portray widespread instability outside of China and thus legitimize the Chinese system. This may taint long term perceptions of China from one side, and cement an “us versus the west” narrative on China’s side, she explained. “All leading to less communication at a time when we need to understand the other side even more deeply,” Yan said.

Testing the World: Assessing China’s COVID-19 Diplomacy

Our second panel, on June 20, focused on China’s Covid-19 diplomacy and was run by Young China Watchers. Chaired by Will Heidlage, head of Young China Watchers in Washington DC, the discussion featured China experts worldwide, who shed light on the multiple meanings behind China’s mask diplomacy.

The discussion opened with Europe: “Visibility was the key,” said Lucrezia Poggetti, Analyst at the Mercator Institute for China Studies in Berlin. “It looked like Italy was left alone by everybody but China.” Beijing created a media narrative revolving around the concepts of gratitude and friendship, but the European Union is still sceptical about China’s reliability, she said. In 2019, Brussels described China as both a strategic partner and a systemic enemy, she recalled, adding that it may now be the time for a more consistent foreign policy.

Visibility was also crucial to China’s strategy in Africa, where “the virus has been the chance for China to rebrand as a benevolent and responsible power,” explained Yunnan Chen, Research Officer at the Overseas Development Institute in London. But African problems are more economy than health-related: the pandemic had devastating effects on African economies, Chen said. As the single largest investor in the continent since 2017, China’s post-Covid test in Africa will be dealing with debt, Chen added.

It’s also crucial to discuss China’s role in South East Asia, noted Prashanth Parameswaran, head of the Bower group Asia and the Wilson centre. “In South East Asia, China was already seen as the major economic partner and security- provider in the region before the pandemic” said Parameswaran. “This trend may be reinforced by the Covid-19 diplomacy.” The elites of most countries have publicly appreciated China’s supplies as a symbolic message of friendship, but the public is still resentful of the costs of the Belt and Road Initiative: Chinese loans may be hard to repay during the post-Covid recession, he added.

China-Latin America relations expert Natalia Cote Muñoz, of the Council of Foreign Relations in New York, also gave her take. “Covid diplomacy is not likely to reshape China-Latin America relations. The region will continue to be only complementary to China’s strategy and the public’s mixed feelings for China will not make the picture any clearer, she explained.

Overall, with mask diplomacy China may have found a chance for political dialogue abroad, but when it comes to the public scepticism and criticism are still on the rise.

See a recording of the digital panel here.

Navigating China’s Narrowing Information Flow

In the third event of the series, coordinated by Chinese Storytellers, panelists discussed China’s sophisticated formal and informal systems of information control and the diminishing channels of information flow in and out of the country.

The panel was moderated by Zhaoyin Feng, the U.S. Correspondent for BBC World Service, who talked about nationalistic voices spreading both top down and bottoms up on social media platforms, such as YY and WeChat, and how the platforms’ isolated nature makes it nearly impossible to fact check their content.

Kecheng Fang, an assistant professor at the School of Journalism and Communication at The Chinese University of Hong Kong, echoed this observation and added that increased censorship activities is matched with augmented propaganda tactics, such as the deployment of the 50 cent party, who either create favorable commentary on behalf of the CCP or troll those whose opinions are at odds with the party leadership. Unlike other previous crises such as the Sichuan earthquake and SARS outbreak, the Covid-19 pandemic is happening alongside widespread social media usage that’s fed increased polarization and trolling, pushing opinions into more private spaces. These tactics can backfire when the CCP is trying to gather public sentiment, uncertain if true opinions have been censored or if seeded propaganda has been gathered as facts.

Censorship in China started very soon after the start of the Covid-19 pandemic, as early as December 31, 2019, only one day after whistleblower doctor-turned-martyr Li Wenliang privately sounded alarm about a mysterious disease, according to Lotus Ruan, a researcher at the University of Toronto’s Citizen Lab. Censorship grew from there and was indiscriminate and widespread, resulting in factual and neutral information from state media being censored as well, she said. Lotus also pointed out that this is usually the result of platforms self censoring, and therefore over-censoring because no one knows where the line is. This points to an arbitrariness that, by design, creates uncertainty and fear.

Amy Qin, an international correspondent for The New York Times who was expelled from China in March, recounted her reporting trip to Wuhan in January where she was able to talk to locals with relative freedom, taking advantage of this small window of opportunity to do in-depth reporting, alongside domestic publications such as Caixin, Yicai, and Sanlian.

In response, Kecheng noted that local Chinese readers also rely on foreign media to learn more about what is happening in China. With journalists like Amy now having to report from outside of China, accurate and nuanced information will become increasingly limited to citizens of all sides. This may further perpetuate the reputation of China and its diaspora as the “foreign other,” Kechang warned.

About the authors

Daisy Singh-Greaves is a writer and copyeditor for NüStories who also helps coordinate the NüVoices London Chapter. She is a British journalist who has written for Panda Radio, among other China-focused media outlets. Passionate about Chinese literature, community-based storytelling and international development, she holds a dual honours undergraduate degree in Chinese and English from SOAS, University of London. Alongside studying for a year at Beijing Normal University, she volunteered at the Starfish Project—a charity supporting and rehabilitating trafficked women in East Asia. Daisy hopes to elevate the voices of women and other minorities by illuminating their stories through grass-roots journalism. Follow her on Twitter @daisygreaves

Silvia Frosina is a postgraduate at SOAS, University of London and a freelancer focusing on politics, civil society and gender in East Asia. Her work regularly appears on the world news section of Italian newspaper Il manifesto (www.ilmanifesto.it) and online at China Files (www.china-files.com).

Cindy Gao is a board member and one of the podcast hosts at NuVoices. She holds a BS from Columbia University.

About the editor

Jessie Lau is a journalist, researcher and artist from Hong Kong covering identity, human rights and politics—with a focus on China and other parts of Asia. Her work has been published by Foreign Policy, Channel 4 News, The Nation and The Economist, among others. She serves as a Board Member and Online Editor-in-Chief at NüVoices, and was formerly a reporter with the South China Morning Post. Website: www.laujessie.com. Twitter: @_laujessie