BY MEGAN CATTEL

*Note: Spoilers ahead *

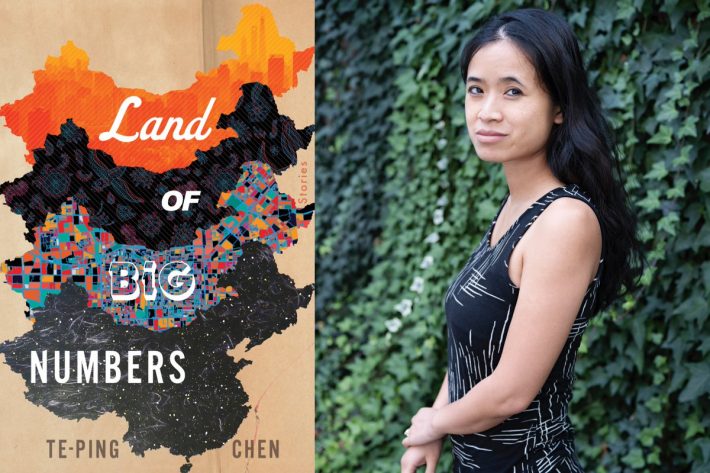

The title of Te-Ping Chen’s debut short story collection Land of Big Numbers conjures up familiar tropes about China, the world’s most populous nation—often spoken about in regards to its massive geographic and economic scale. We see this in media too, the lens zooming outward to capture packed train stations during Lunar New Year travel, or a viral video of 700 students dancing in the schoolyard, perfectly synchronized. The focus is typically on the crowd, the uniformity, the collective.

But throughout the ten stories in Land of Big Numbers, Chen – a founding member of NüVoices – sketches out the interior lives of her protagonists who live in (or have connection to) modern China: a man determined to strike rich in the Chinese stock market, a migrant worker employed at a flower shop who is infatuated with a customer, and a government employee being stalked by her ex-boyfriend. We meet characters that fall all along the political spectrum, from a farmer eager to gain admission to the Chinese Communist Party by inventing a noodle-chopping robot to a young woman who becomes an online dissident.

Inspired by her years as a foreign correspondent in Beijing and Hong Kong for the Wall Street Journal, Chen, a Chinese-American journalist, drew upon stories from people only mentioned in news reports. I’ve always had a soft spot for writers who move between journalism and creative writing, who recognize the limitations and advantages of both forms. In interviews, Chen has discussed feeling “liberated” when working on these short stories during her spare time, to dive into the personal inner-workings and motivations of her characters. Listening to these interviews, I couldn’t help but recall Lisa Ko’s novel The Leavers, a book inspired by a New York Times report about a Chinese New Yorker held in ICE detention, or Arundhati Roy’s insistence on needing both fiction and non-fiction to do her work justice.

Deft at the short story form, Chen’s tales don’t linger on one moment for too long. There are beautiful details the artful reader can appreciate (croissants that are “warm and soft and many-layered as you pulled them apart, like the underbelly of a sea creature gently exhaling,” for instance) Then there is the political subtext: in one story, a side character is described as a hardworking government employee, picking up extra shifts in “transport,” a succinct detail quickly glossed over and easy to miss for speed-readers. Later, we learn that “transport” refers to driving protesters to detention centers. Another story depicts a dingzihu or “nail house,” which refers to an abode that homeowners refuse to move out of when developers flatten their neighborhood with the aim of turning it into a shopping mall or subway station.

Then there are details Chen has chosen to insert, familiar to those who have spent time in China before: “a hulking green locomotive,” a reference to the slow freighters built in the 1950s being phased out by China’s high-speed rail, “hawthorn impaled on sticks and sheathed in frozen yellow sugar casings” a description of tánghúlu 糖葫芦, a popular winter snack, and a wedding banquet platter with “swans made of mashed-up radishes, with carrot beaks and black sesame eyes.”

In “New Fruit,” a magical citrus (called ‘qiguo’) brings back joyful and tragic repressed memories when consumed, fictional singer Carina Wei croons a “treacly single played everywhere” entitled “My Sweet Qiguo.” Perhaps a nod to Teresa Teng, a wildly popular singer from Taiwan whose love ballads were banned in the Mainland for causing “spiritual pollution” in the 80s. Like with certain books, songs, and websites banned throughout certain time periods of Chinese history, qiguo is also banned by the story’s end.

Somewhat selfishly, I dove into Land of Big Numbers wanting some of the characters, nestled in these alternate realities, to maneuver the system unscathed. Maybe fiction could act as a buffer between readers and China’s current state of authoritarianism. But this collection is firmly rooted in realism, despite surrealist tendencies. Reading chronologically however, the very last story nudges the reader toward a cliffhanger ending, leaving room for possibility.

In “Gubeikou Station,” a bureaucratic rule leaves dozens of subway passengers stranded on the platform. The protagonist of the story, Pan, is determined to escape. Days turn into weeks, then months. The story follows several characters as they make due with the maddening circumstances. Strangers turn into friends and caretakers. A community forms, and early attempts at rebellion dissolve. Some characters acquiesce quickly and others erode over the course of the story. But Pan never truly gives in. It was easy for me to root for her, and ultimately, the ending of the story leaves Pan’s fate up to the reader’s imagination.

While Anglophone books on China have typically been centered on the country’s history and politics, more diasporic and transnational authors are coming to the fore in publishing, a welcome addition to stories about the Cultural Revolution and Chinese science-fiction. Readers of Xuan Juliana Wang’s Home Remedies and Yiyun Li would take great delight in the stories found in Land of Big Numbers.

About the author

Megan Cattel is a NYC-based writer and journalist. Currently an intern at SupChina and St. Louis Public Radio, she has written for NeoCha, Goldthread, and NüVoices and was a summer fellow at the Center for Public Integrity in 2020. A graduate of Columbia Journalism School, Megan covered immigration for Uptown Radio, Columbia’s weekly radio show. Follow her on Twitter and visit her website.