BY EMILY MATSON

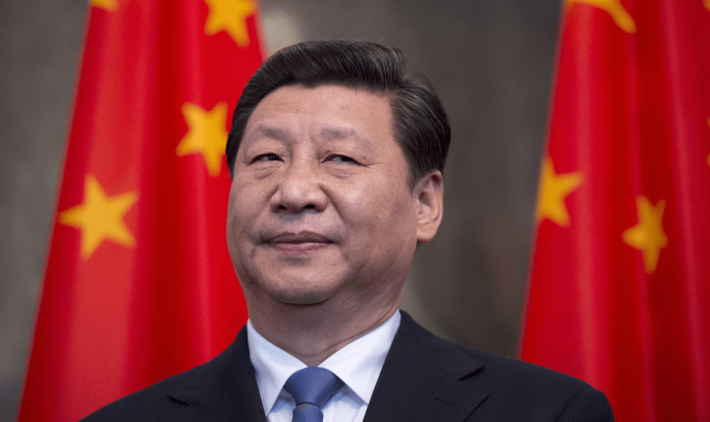

As Xi Jinping prepares to cement his power through a much-hyped third term as China’s president, many observers have been quick to compare his leadership with that of his revolutionary predecessor, Mao Zedong. Now, as the 20th National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) rapidly approaches, some commentators are even claiming that “Xi has surpassed his goal of becoming the new Mao.”

While it may be true that Xi has consolidated more political clout than any leader since Mao, drawing too close of a connection between the two leaders is misleading. Although Xi has selectively capitalized on Mao’s legacy for his own political gain, Mao’s rhetoric and vision for 20th century China differed considerably from Xi’s 21st century “Chinese dream.”

In a recent seminar I taught at the College of William and Mary on the “Life and Legacy of Mao Zedong,” one of my students aptly noted: “there are as many Maos as there are individuals who study him.” Indeed, Mao Zedong is one of the most – if not the most – contentious figures in modern Chinese history. Either vilified as a tyrant or venerated as a revolutionary, Mao has a reputation that often veers toward extremes in popular cultural representation. Even after his death, however, Mao has continued to serve as a key bedrock of legitimacy for CCP leaders.

Following Mao’s death and the subsequent end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, the legacy of the “Great Helmsman” was questionable, to say the least. Should Mao be remembered as the visionary revolutionary who birthed the People’s Republic of China (PRC), confidently proclaiming in 1949 that “the Chinese people have stood up”? Or would his memory forever be tarnished by the tragic death of millions in the Great Leap Forward and the Cultural Revolution? Deng Xiaoping, the leader who followed Mao, struck a balance. Although he admitted that “Comrade Mao was not infallible or free from shortcomings,” he also emphasized that “were it not for Chairman Mao there would be no new China.”

After Xi took the presidency in 2012, pundits have pointed to his burgeoning cult of personality as well as his increasingly authoritarian rule when likening Xi to Mao. Particularly after his political ideology “Xi Jinping Thought” was first added to the PRC constitution in 2017 and presidential term limits were abolished in 2018, Xi has been widely called the “most powerful Chinese leader since Mao.”

However, after superficial comparisons are made, myriad differences remain. For instance, what makes comparing Xi to Mao intellectually lazy, as historian Rebecca Karl puts it, is that “Mao’s and Xi’s historical projects couldn’t be more different.” Whereas Xi’s “national rejuvenation” agenda focuses on building up Chinese wealth and power both domestically and abroad through nationalism, Mao was more concerned with utilizing domestic class struggle to create an egalitarian, socialist society through revolutionary means.

In his famous “Report on an Investigation of the Peasant Rebellion in Hunan” in 1927, Mao proclaimed: “A revolution is not a dinner party, or writing an essay, or painting a picture, or doing embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained, and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.”

Here, Mao advocated revolution via the means of violent class struggle. This revolution would not benefit all Chinese equally; rather, the peasants (i.e., the “semi-proletariat”) would overthrow the landlord class and its allies among the bourgeoisie in order to advance society towards the ultimate goal of a communist utopia.

Contrast this with the following excerpt from Xi Jinping’s 2021 speech to celebrate the CCP’s centenary: “We must strengthen the great unity of the Chinese people. In the course of our struggles over the past century, the Party has always placed the united front in a position of importance…The patriotic united front is an important means for the Party to unite all the sons and daughters of the Chinese nation, both at home and abroad, behind the goal of national rejuvenation.”

Gone is the Maoist emphasis on violent class struggle. In contrast, Xi highlighted the national unity of the Chinese people, regardless of socioeconomic class, and portrayed the CCP as working for the benefit of all Chinese.

Unlike the Red Guards in the Cultural Revolution, diehard Mao fans today will not find unquestioning support from Xi Jinping and the top echelons of Party leadership, who are more interested in establishing the authority of the Party than aiding dissidents in fomenting revolution.

This is evident in the treatment of many “neo-Maoist” groups that have formed to protest what they see as China’s current capitalist excesses and widening socioeconomic disparities, among other issues. Rather than be embraced for their revolutionary credentials, these leftists have faced strong pushback from the state, particularly leading up to sensitive Party events.

Whatever the pitfalls of comparing Xi and Mao, it is clear that China’s current leader continues to utilize the latter’s legacy to increase his own prestige. Under Xi’s watch, all university students must now take a course on Marxism and its applications in China (it highlights Xi Jinping Thought, in essence a compilation of Xi’s speeches as they relate to China’s military and economic rise). Xi himself has paid homage to Mao twice – most recently for the 2019 commemoration of the seventieth anniversary of the founding of the PRC, when he bowed before Mao’s remains in the Tiananmen Square mausoleum. However, in a fashion similar to how Putin tiptoes around Lenin’s memory in Russia, Xi remains wary of Mao’s more incendiary rhetoric. Whether Xi can continue to selectively promote Mao’s memory to bolster his agenda while discarding Mao’s inconvenient calls for revolution remains to be seen.

About the author

Dr. Emily Matson received her PhD in Modern Chinese History in fall 2020 from the University of Virginia. After graduation, she was a Wilson Center China fellow, taught East Asian History at the College of William and Mary, and is now teaching at American University. Her research interests include Northeastern China (东北), the War of Resistance against Japan (抗日战争), historical memory, and museums. Dr. Matson has extensive teaching experience and recently created two new freshman seminars at William and Mary: “Historical Memory of WWII in East Asia” and “The Life and Legacy of Mao Zedong.” Visit her website