Read an exclusive excerpt from Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You by Candice Chung:

Those first few years in Sydney, my sister and I cooked like the reclusive middle-aged men in Haruki Murakami’s novels—grouchily, on our own. We had one signature dish. Or was it many? The point is, by the time we started high school, we could make anything that had Spam in it.

Not all mystery meats are created equal. Our brand of choice was Ma Ling Premium Luncheon Meat. I liked the white-and navy tin, the cursive writing, the kitschy artwork that revealed a blushing, mid-carved bit of square meat, made fancy with a cucumber salad garnish. Our family is loyal to Ma Ling the way

some folks are loyal to their football teams.

But here’s what most people don’t know about Spam: it’s all about making the right cut. You need a dice for omelettes; lengthwise cuts for breakfast fry-ups; and widthwise to stew with tomatoes, so that the ham-like blocks soften and their saltiness mellows. Thin squares are best for sandwiches—a gateway to the ultimate crisp-soft-crisp experience. Knowing this separates amateurs from old hands. At eight and twelve years old, my sister and I already considered ourselves experts. Being Spam masters also meant we had full control over our dinners, lunches and breakfasts any time Mum couldn’t get out of bed—a phenomenon that was entirely new to us.

Nirvana wasn’t the only thing we’d never heard of in the mid-nineties. No one in our family had heard of depression, either. At least not the way it forces you to sleep in, drains you of energy and pins you to the television because ordinary life makes as much sense as mindless daytime soaps. Mum never once said she was depressed. All my sister and I knew was that we needed to fill our own stomachs when she couldn’t find the energy to hang out with us or cook, which was happening more and more often.

That first year in Sydney, the year of Mum’s frozen sandwiches, we could’ve built ourselves a new room with the blue-and-white tins. Already we’d grown wary of the suburban quiet, the footdragging sun, the waft of eucalyptus in the air that reminded my sister and I of the smell of spit. A few weeks into the move, we braced ourselves for Dad’s flight back to Hong Kong. There were loose ends to tie up, Mum and Dad told us. He would be gone for a while. There is a Cantonese term for this: 做太空人—being an astronaut family. When one parent or partner, usually a man, lives in the liminal space between their old world and the family’s new home turf.

‘Why astronaut?’ my sister and I asked. When it was clear that we were the ones playing aliens. I remember the dream logic of a new country. The way the strangest things weren’t always the most exotic, but the warped versions of what we once knew. That first year, I couldn’t wrap my head around the oversized bak choy in the supermarkets, how kids played with tennis balls in driveways with their bare hands, the way people said ‘tea’ when they meant dinner. ‘You right?’ a burly, bearded man once snapped at us at a newsstand—two familiar words that were drained clean of meaning all of a sudden.

We stayed silent, confused by his irritation. Not knowing that we’d just been told, You’re in the way. Hurry up. Right before he left, Dad spotted a new Cantonese barbecue joint in the neighbourhood. The siu laap po was right across the road from our train station. This meant we would be able to get decent barbecued meat within walking distance—an alternative to Spam, which by then was the only food my sister and I trusted.

‘Not bad, right?’ He beamed at his own discovery. That weekend, as soon as the newspaper on the shop window came off, Dad paid Kam Kee a visit. The queue would be long, he figured. We were to stay home, get some rice ready and wait for him to return with the goods. I pictured him scanning rows of soy chicken, glossy roast ducks and my absolute favourite thing: the sweet-salty char siu, hung up like wind chimes in the sun.

We were sitting at our fold-out table by the time Dad got back. It was five o’clock, 5.30 at the latest. We stared at the takeaway boxes in his grocery bag. A few smaller, round boxes of dipping sauces peeked out. Success. Dad wiped his brow with a handkerchief and straightened out bits of damp hair with his pocket comb, the way he did right before a big meeting or on special nights out. He peeled open the

plastic lid and plated up the still-warm meat.

‘Sik faan!’ Let’s eat. The colour of the pork was unmistakable. But I was confused. Instead of a charred, honey-glazed surface, this char siu was a dull red. The pieces of meat were cut jaggedly—not delicate slices, but thick, eraser-sized. I looked at Mum, then my sister. For a moment, the three of us fell quiet.

Dad picked up the first piece and gave it to Mum. Then one for me, and my sister. He took a bite himself, to confirm what we already knew. I chewed the stringy pork and felt my chest tighten.

‘Look,’ he announced. ‘By the time I get back, this shop is going to make better char siu than the siu laap po in Hong Kong.’ This seemed plausible, as none of us knew exactly when he was coming back. At the table, my head began to throb. He chose to move to this place and he is leaving. I did not choose but I had to stay. The thought of being trapped in this upside-down life made me nauseated. I felt a violence of disappointment from my temples to the tips of my fingers. I sat on my hands and tried not to cry or throw up.

‘We won’t miss you,’ I said.

‘Good.’ Dad’s face was unmoved. He looked away from the table, then reached for another piece of char siu and rested it in my bowl. This time, he gestured at the small container of plum sauce. And we ate it all. Every last piece of the terrible pork.

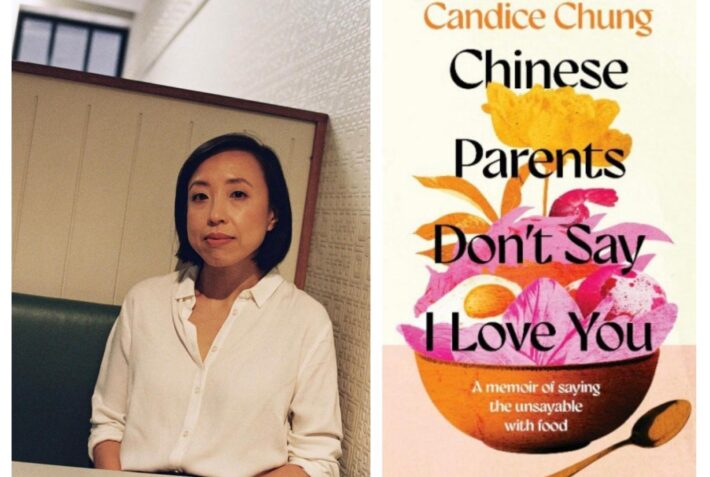

About the author

Candice Chung is a Glasgow-based writer, editor and former restaurant reviewer for The Sun Herald. Her work has appeared in The Sydney Morning Herald, Good Food, The Australian Gourmet Traveller, The Guardian, Gutter, best-selling food author Hetty McKinnon’s Peddler Journal and more. She is a founding member of Diversity in Food Media Australia, which supports and promotes underrepresented voices in food. Her story ‘Why Chinese Parents Don’t Say I Love You’, first published on The Sydney Morning Herald, generated more than 2 million page impressions.