BY HEATHER IRVINE

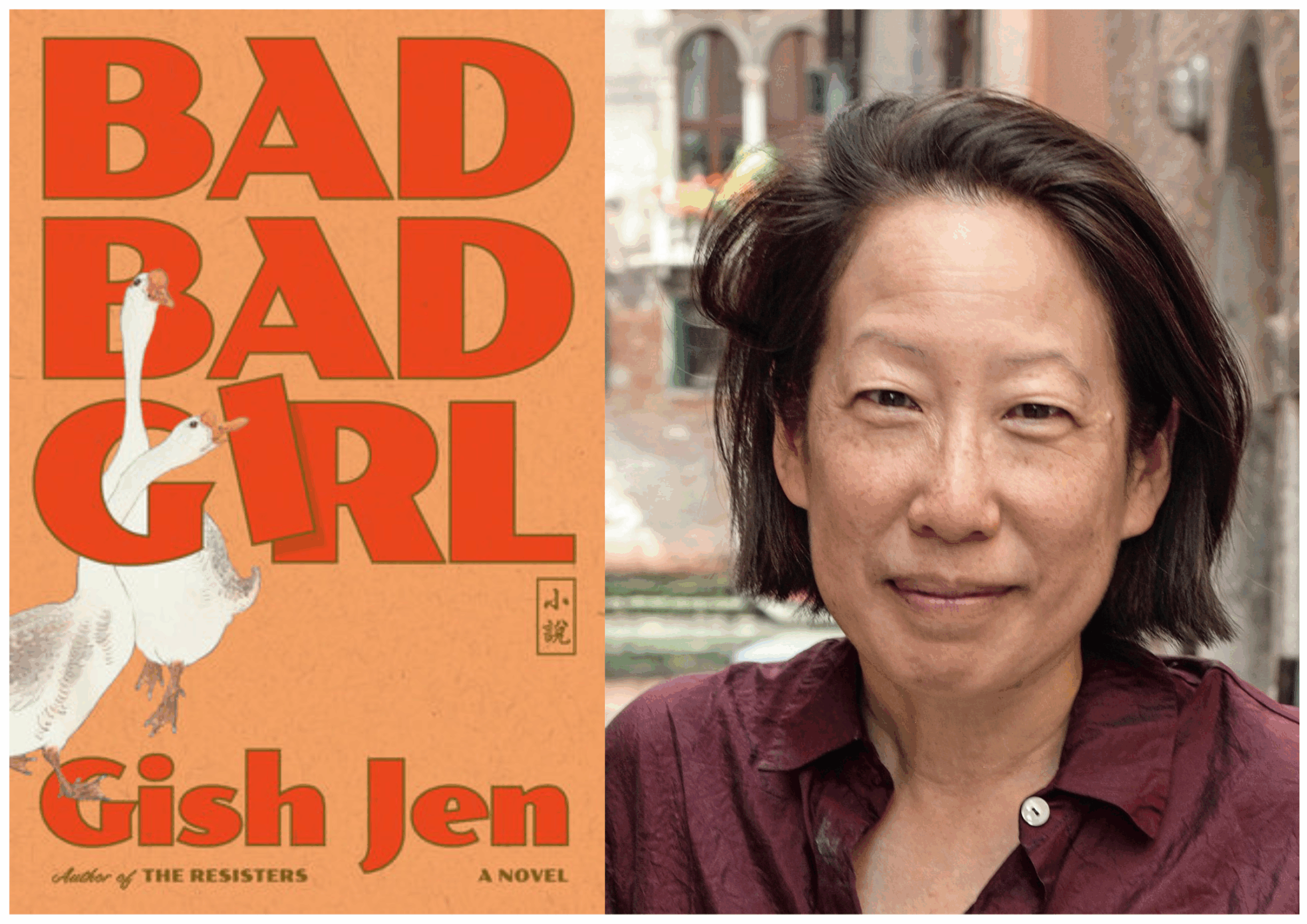

Gish Jen’s latest book has been her hardest; she confesses so in its closing pages. But—”It’s what I need to do—as if I am finally burying you, or trying to.” Bad Bad Girl, Jen’s tenth book, fictionalises her dead mother’s life to probe their fraught relationship. “If I write about you, if I write to you, will I understand you better?”

Bad Bad Girl blends genres: is it a memoir? A novel? An auto-fiction? Jen’s mother left behind ‘very little textual evidence’ the writer could use, mainly professional teaching notes, and cautiously-worded letters from family in China, as she tells the Washington Independent Review of Books. Jen therefore prefers to call the book a novel, seeking emotional truth as she builds a fictionalised account of her mother’s childhood in Shanghai under Japanese occupation, her arrival in the United States as a graduate student and failure to complete her PhD after marriage and motherhood.

Although Jen has made her name writing about immigrant experiences, and generational conflicts within self-reinvented families, Bad Bad Girl, with its sombre, introspective mood, is a tonal switch from her forensically comedic story-telling. Her first novel, Typical American, showed a Chinese family morphing from quizzical visitors into immigrants when the 1949 Communist victory traps them in the US. They soon acquire habits they previously disparaged. In World and Town, it is the American idyll that is in crisis, as arrivals from Hong Kong and Cambodia seek a peaceful small-town life.

Jen’s mother was known by several names. As Loo Shu-hsin, she was the daughter of a wealthy Shanghai banker. As Agnes Loo, she travelled to New York pursuing her dreams of graduate school, staying on after 1949 when the Chinese Communist Party came to power. Her marriage made her Agnes Jen, Chinese immigrant and mother of five. Bad Bad Girl is split in two parts to reflect her shifting identity: Part I centres on Loo’s life before the writer’s birth, while Part II shows her impact on Jen’s life as a withholding, unyielding mother.

Loo’s mother was cruel and neglectful. She dismissed Loo from birth—she wasn’t a boy, a ‘”number one son,” and so failed to meet traditional Chinese ideals—and derided her intelligence, saying “It’s no good for a girl to be too smart, who will marry her?” A nursemaid whom Loo called ‘Nai-ma’ gave her love and care, breastfeeding her and sleeping alongside her every night until, one day, Loo’s mother fired Nai-ma without warning. Loo never saw her again. Jen portrays Loo’s devastation with deep sympathy and frames the loss as one of many traumatic factors that shaped Loo’s failings as a mother to her.

The main narrative is continuously interrupted with fragments of imagined dialogues where Jen and her dead mother discuss the story as she writes. Loo’s scathing voice haunts Jen as she wrestles the family story onto the page. “Bad bad girl!” Loo scolds. “You don’t know how to talk!” These words arise each time a daughter speaks—or writes—out of turn, binding together two generations of mother-daughter conflict. Loo heard them from her own mother. “With a tongue like yours, no one will ever marry you.” They score a pattern: a sharp-minded daughter, unashamed of her own intelligence and bold enough to talk back, grows into the nemesis of a mother who cannot bear have her authority challenged. Jen recalls telling her mother Kennedy had been shot:

“You think you know everything,” she said.

– Bad Bad Girl by Gish Jen

“But he was!” I said. “He was! You should turn on the TV!”

And when the TV said the same thing, she said, “You have too much to say.” And, “You have to learn how to talk.”

“You have to learn how to listen!” I shot back. “You do! You have to learn how to listen!”

But that just made her yell, “Since when does the mother listen to the daughter?”

Jen recognises this intergenerational pattern and reflects on Loo’s experiences as victim and as perpetrator. Her sympathy for her young mother saturates the book’s first half. The narrative is woven around Loo’s point of view, in league with her feelings, responses and connections to people. The narrative voice is on Loo’s side, in a way that Loo rarely ever was for Jen. When Loo meets criticism from one of the few people she knows in America, Jen says: “She hadn’t cried when she left China; she hadn’t cried on the long, lonely ship ride; she hadn’t cried as she wrote to her family. She hadn’t cried at the cruelty of the Japanese occupation, or […] at the injustice of her brother being put ahead of her, all her life, at every turn. But now at this nothing, she cried as if she were a little girl and Nai-ma had been taken from her all over again.”

Jen’s choice of life as a novelist has enabled her to do what Loo refused to do in all their long battles; to understand where the other person is coming from—how they feel, who they are. “Is that why I am writing this, so I can remember my mother fondly?” Jen reflects towards the end of the book. “Am I inventing as much as remembering her? Erasing as much as preserving her?” The mother-daughter dialogues keep Loo alive, with all her judgement and hypocrisy, if only to make room for reappraisal.

Unfortunately, they are dense with historical context and clunky exposition, at least early on. Jen’s side of the conversation with her dead mother details the atrocities the Japanese occupiers committed against Chinese people, and yet more killings and mass starvation during Communist reforms. Too often in these imagined exchanges Jen speaks solely to deliver information to an American audience. This information would be better in the main body of the narrative, not forced into the shape of conversation.

But the imagined dialogues shine in the book’s second part. When Jen is born into the family story, the narrative voice shifts to centre her consciousness and experience. Now, the dialogues resemble a courtroom where mother and daughter adjudicate differences so stark they’re still arguing across the grave. Usually, they end in stalemate. American ways versus Chinese ways. “You ask anyone in China,” Loo’s voice will argue. “But here, Mom,” Jen returns. Once Jen enters the plot, the presence of her voice in both narrative strands—the dialogues and unfolding events—facilitates discussion of abuse’s circularity: “Because people have been known to replay things. Victims will become perpetrators. The bullied will become bullies.” Writing both her mother’s story and her own lets Jen step outside her anger and adopt an author’s psychological inquiry.

What is most impressive about Bad Bad Girl is Jen’s movement between (and layering of) her roles as author and as daughter. She began early. “Lillian Jen” discovered she could not identify her writing self with “the nice Chinese girl my mother had wanted.” To reinvent herself, she took the nickname “Gish” given by her high school creative writing club, after silent screen actress Lillian Gish. “‘Gish Jen’ would go on to publish everything else I wrote—becoming a person who was, above all, not [my mother’s] daughter” Here, she highlights the book’s forked consciousness; a daughter reconciling herself to the ‘mother-shaped hole in [her] heart,” and the author who tries to present all perspectives.

Jen pierces through her own rage and grief to bring to light the burnished core of regret that hardened and embittered her mother. Jen sees her mother mourned the life she had dreamed up for herself when she crossed the sea to America: “A life where I was lucky, yes. Not just the luckiest one in an unlucky family, but lucky.”

Despite Loo’s emotional detachment and derision, her intolerance for having her authority as a mother questioned and occasional outright cruelty, Jen retains admirable writerly compassion for her. In old age, Loo expressed her pain by reciting melancholic lines from a Tang dynasty poem. “How typically Chinese, to express her distress through poetry. In China, anyone in her family would have understood her. And yet who now understood what she was trying to say? My poor mother.” Through words, poetry, storytelling, Jen extends a sympathy which stands in place of a loving connection with her mother. In the end, Bad Bad Girl is a book that fulfils that most classical of Chinese ideals, filial piety.

About the writer

Heather Skye Irvine is a writer interested in art and literature as objects saturated with the potential for cross-cultural understanding. She was born and raised in Hong Kong and aims to emulate the city’s melding of East and West in her writing. Find out more on her website and LinkedIn.

About the editor

Mary Hennock reported for the BBC from London then as Beijing correspondent for Newsweek. Her work has also appeared in The Guardian. She now works primarily as an editor on in-depth reports with a China focus.

Photo credit: Basso Cannarsa