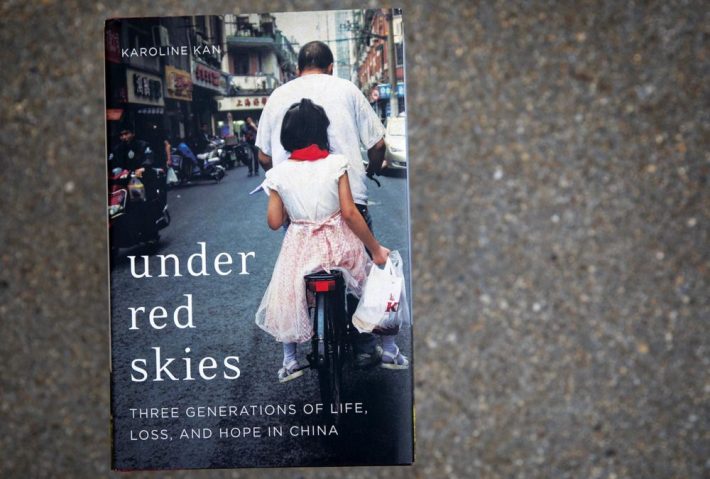

In her debut book, Under Red Skies: The Life and Times of a Chinese millennial, former New York Times reporter Karoline Kan offers a deeply personal and powerful portrait of China’s conflicted past and present.

On May 31., Kan – also board member and editor at NüVoices – will be speaking about her book at an upcoming event co-hosted by NüVoices and Young China Watchers London at King’s College London. PLEASE RSVP VIA EVENTBRITE!

Raw and revealing, Kan weaves together the stories of three generations of her family, as she describes the extraordinary daily poverty and political unrest that make up Chinese life in the past century. Born in 1989 as an illegal second child under the One-Child Policy, Kan grew up in Tianjin and now lives in Beijing. Her mother, a strong, fearless schoolteacher, risked everything by giving birth to Kan. Her grandmother, who married at age fifteen, fought to make a way for her family during and after the Great Famine. Kan’s own story now, an ambitious millennial navigating career and love during a time rife with social change, is intimately connected to the stories of older generations and China’s jarring past.

Globally, the voices of young Chinese women are often neglected. In recent years, several books have attempted to profile Chinese millennials but all have been by foreign authors. UNDER RED SKIES is the first English-language memoir from a Chinese millennial to be published in America. The real China, Kan shows, is not only what is shown in the daily news cycle.

Based on oral histories passed down to her, as well as hours of interviews, diary notes, day-to-day conversations and her own lived experiences, Kan has created a skillful narrative that brings readers into the lives of these brave women as they break the chains of tradition in search of a better life. Kan’s family portrait reflects the shifting sands of China and reveals how the past has shaped China into the powerful nation it is today.

A Conversation with Karoline Kan

Q: Jung Chang’s bestselling memoir, Wild Swans, has become a modern classic since its publication in 1991. Your memoir also recounts stories of women from your generation and of those older than you. Why are their stories, and yours, important to the understanding of China today?

A: My generation in China has been labeled, variously: the spoiled, the apolitical, the generation of little emperors and princesses, the materialists, the young nationalists and the selfish. You can’t make such sweeping generalizations – to say an entire generation is like this or that; however, I think many of these labels make sense in some ways. We are more divers than our parents and grandparents’ generation, who often self-describe themselves as “hardworking”, “responsible”, “money-saving”, etc. “Bitter-eater” is a popular term used to describe those who sacrifice; they are martyrs and good examples to past generations but my generation feels differently about how we should live and what should motivate us. I want to show readers the huge gap between the older and the younger generations, and the best way to do this is by telling their stories. I think to understand China, you have to understand and see the interactions between the different generations.

Take my own experience: like many of my friends, I grew up spending a lot of time with my grandparents because they were my caretakers while my parents worked. From them, we learned of the hardship, what was it like in the war, how they survived when starving – things like that. Because the older generation experienced the hardship, they didn’t want it to happen again to their children.

As their lives improved, they tried to provide as much to us as possible. They witnessed the darkness and the danger of politics, so they warned us to keep a distance from politics. And no matter how reluctant we try to resist their way, we are influenced by them.

Q: You’ve pitched this as a look at contemporary Chinese history. Why is that important? What’s been missing in the global narratives or discussions about Chinese history that you present in Under Red Skies? Is there reluctance or fear from Chinese people to tell their stories in the West?

A: There have been other books written by westerners about China and Chinese people; or books about famous Chinese people and families translated from the Chinese. They are good, but I always felt there was an absence of voices from the ‘common’ people, especially the voices of women. My hope is that by telling my family’s and my own “micro history”, readers can better understand the “macro history” of our country. I come from a typical Chinese family from a small town. I grew up and was educated in China, so my perspective, coupled with my experience as a journalist writing for foreign media, gives my already unique perspective an even greater advantage: I can give an insider/outsider point of view. I am also the rarely heard voice of a young woman writing from and about China.

While I was researching and preparing the book, I tried to “interview” my relatives, but they were reluctant, not because they didn’t want to share, but because they are not used to being interviewed. Chinese people, especially the older generation, remember what it was like to get into trouble – often imprisonment – for what they said during the years of government suppression so, when facing strangers, they sometimes hide their emotions and choose carefully what they say. To find the real stories and uncover their emotions, you have to be somebody they trust. At the same time, the censorship in China makes it difficult for Chinese language writers to touch upon social and political issues, but I think those “sensitive” issues are important to every Chinese family. The fact that this book is written in English helps me avoid government censorship.

Q: How have American politics inspired Chinese women in the women’s movement and in advocating for women’s rights? How have things shifted between your generation and your mother’s? (How do you think the stories in Under Red Skies will resonate with young women in the US and abroad?)

A: Chinese people follow the international news and care about American politics much more than you could imagine, although the news and information is not always accurate if they don’t read original reporting in English. Many Chinese young people are acting as a bridge, connecting American culture and politics to Chinese people. The young generation travel more, read English, and grew up with Western culture. The development of social network platforms also helps. The #MeToo Movement is a good example of how the lives of young people in China today are related to those in the rest of the world.

A few months after the #MeToo movement began in the US, female students in Chinese universities began to publicly accuse some very well-known and respected scholars of sexually harassment. It marked China’s #MeToo movement and, from then on, dozens of other men from the worlds of academia, media and even NGOs were accused of sexual harassment and misconduct including rape. The #MeToo movement in the US gave young women in China strength and inspiration to speak out. This is mainly, if not exclusively, happening among the millennials. Such things were more difficult for my mother’s generation to speak out about and against. Instead of speaking out against the One-Child Policy, my mother took action on her own and also suffered alone because of it. Most women of my mother’s generation knew of no alternative than keeping silent when their rights were violated. There are still huge difficulties; feminist activities are always banned and punished, but we continue to push.

Q: What do you think Chinese young people are most frustrated about today?

A: Chinese young people are frustrated about many things: the stagnating social mobility, which makes it harder to climb the success ladder as our parents’ generation could; the fact that older values and customs, such as those concerning marriage and family, still reign; the rapidly widening gap between rich and poor during a time when the country has become increasingly capitalistic, with advertisements flaunting before us a glowing material world out of our financial reach.

For those of us born in the 1980s and 1990s, we used to take it for granted that life would be better and better, that there would be more possibilities and more freedom, but now that we have grown up, we find it’s not always true: unlike the perception of China in the West, Chinese society is not growing more equal where we can all expect to be Crazy Rich Asians; the economic miracle will probably break during our lifetime. My parents’ generation could at least attempt to change their fate, for example, through education. But it’s less easy for the young because richer kids have the advantage now, of starting with a better education. My generation was born after the Reform and Opening Up, which marked China’s opening to the West and economic reform. Many traditions have been fading away, replaced by new culture and information coming from outside. This has confused us and has partly caused the generation gap. My grandparents’ generation experienced the war and many horrible things; my parents’ generation grew up in Mao’s cultural revolution. They all had grand “missions” erected by the states, but my generation had little such direction – it’s as if we are groping for our path in the darkness. We may have this most in common with western millennials.

Q: Do you think of China as a superpower? How has that label affected your life as a millennial and older generations who survived catastrophic events like the Great Famine?

A: China is becoming a superpower, and very influential around the world. But it’s not yet the same kind of “superpower” as the United States. The US is still the only superpower in the world, especially when you take soft power into account. The Chinese economy developed so fast in the past thirty years, and life is changing so hugely that everybody tries to catch up with that speed to avoid being left behind. People like the idea that China is becoming a superpower because the media sells us that humiliation and hardship are now in the past and Chinese people are so eager to be strong and respected, and “national rejuvenation” is a goal that is largely shared and applauded.

Yet while development has made our life better, it has also caused anxiety. My generation grew up without any catastrophic events. Everything seemed very positive, at least on state media: China’s double-digit GDP growth; the 2008 Olympic Games; becoming a member of WTO; the development of national defense system; the space projects…The growing buying ability of an increasingly rich population made China the most attractive market in the world. We millennials grew up with the idea of a strong, mega China and with censorship making it hard to criticize the Party and the government, the young generation are very confident (maybe overconfident sometimes), and when abroad, if they hear anything negative about China, they feel shocked or irritated.

But the older generation, take my family for example, are more cautious with the word “superpower”. For a long time, this word has had negative connotations in China, especially during the cold war. Because of the tragedies they experienced, the older generations are more accustomed to preparing for the worst. They know how things could change overnight, how a superpower like the Soviet Union could collapse suddenly. So the older generation are more conservative, they still save money, and try to stay away from politics.

Q: How have US politics and the Trump administration changed Chinese people’s views of the West?

A: After Trump was elected, people who support China’s one-Party system and are afraid of democracy said things like, ‘Hey, this is what democracy leads to. If we give everybody a vote to elect our president, we might have selected a businessman or someone even worse.” It has also shaken the belief of people who believe in democracy and in the American political system. Chinese liberals had regarded America as a moral model that would fight for ideology and dreams, but slogans like “American First” has damaged their hope. But for the group of people who are anti-America, they are happy, because they believe Trump’s administration would trade anything with China for its “national interest”, without holding to certain principles; for example, they believe Trump’s administration would stop caring about China’s very poor human rights record or stop protecting Taiwan if China’s offers on other issues were attractive enough.

Reproduced with permission from Hachette Books/Karoline Kan.