BY EMILY MATSON

When I first visited the northeastern provincial capital of Harbin to conduct dissertation research, I had never heard the name Zhao Yiman. This was soon to change, as by the end of a particularly sweltering day of fieldwork in mid-July, I was duly impressed by just how large the presence of this CCP female martyr loomed in the city. Sweating profusely and deeply regretting my decision to forego a taxi ride, I strolled down Yiman Street on my search for the Northeastern Martyrs Memorial Hall, the oldest of its kind in the PRC. After passing the Zhao Yiman Monument, I finally arrived at the Memorial Hall. Relieved that there was functioning air-conditioning inside, I meandered through the “Black Earth and Spirit of the Martyrs” permanent exhibit until I encountered an entire subsection titled “Faithful Soldier, Great Mother – Zhao Yiman.”

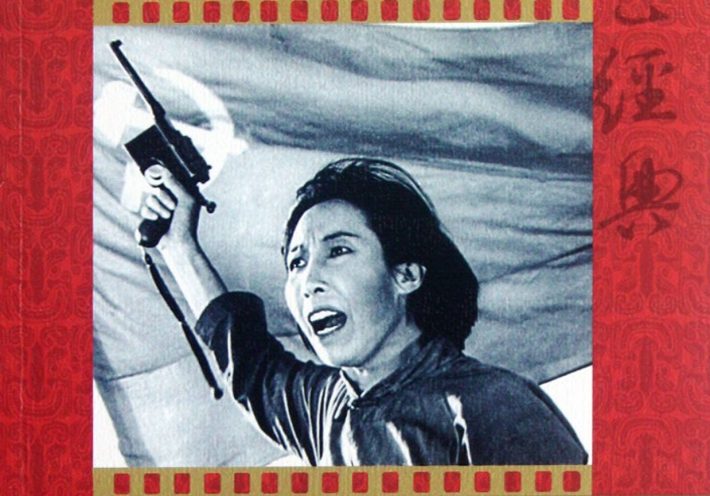

As one of the most lionized female revolutionary martyrs in China, Zhao Yiman is known for her leadership in Northeastern resistance to the Japanese-controlled puppet state of Manchukuo. After joining the CCP in her home province of Sichuan, she was sent to the Northeast after the Mukden Incident of 1931, where she rose quickly in the ranks to become the political commissar of the Second Regiment of the Third Army. In November 1935, after badly injuring her leg in a fierce battle waged against Japanese forces, Zhao was captured while lying unconscious in a remote farmhouse. Subsequently, even after being subjected to the most brutal means of torture, she steadfastly refused to divulge any information to her Japanese inquisitors on the activities or whereabouts of the Northeastern Anti-Japanese United Army. As a result, she was publicly executed at the young age of 31.

Standing in the exhibit, I read the above details on Zhao’s life with fascination, but also with immediate recognition of the revolutionary tropes contained therein. This biographical sketch of Zhao seemed to match up closely with those of male revolutionary martyrs like Yang Jingyu and Li Zhaolin. These men were also “faithful soldiers” that exhibited the laudable qualities of brave resistance, patriotism, and undying loyalty to the bitter end, even to the point of martyrdom. However, after this initial overlap, Zhao’s narrative arc turned out to noticeably diverge from those of the men.

At the center of the subsection, two white columns framed a prominent white bust of Zhao Yiman, situated on a marble black background. Zhao’s resolute eyes peered down at me, further cooling me off from the hot summer day. But what, exactly, was Zhao staring at with such calm determination? What were the thoughts of this 31-year-old as she faced her impending demise? My gaze was drawn next to the gold-embossed text of the plaque below, and I was startled to find that it recounted Zhao’s final farewell letter to her son, Ning’er, which she penned shortly before her execution:

At the center of the subsection, two white columns framed a prominent white bust of Zhao Yiman, situated on a marble black background. Zhao’s resolute eyes peered down at me, further cooling me off from the hot summer day. But what, exactly, was Zhao staring at with such calm determination? What were the thoughts of this 31-year-old as she faced her impending demise? My gaze was drawn next to the gold-embossed text of the plaque below, and I was startled to find that it recounted Zhao’s final farewell letter to her son, Ning’er, which she penned shortly before her execution:

“Ning’er, it is such a shame that your mother has not fulfilled her responsibility of educating you. Because your mother has persisted in the struggle against Manchukuo and the Japanese, today is already the eve of her sacrifice. I hope, Ning’er, that you will quickly grow up, and come to comfort your mother under the ground. After you have grown up and reached adulthood, I hope you will not forget that your mother sacrificed herself for her country!”

This, then, showed the “great mother” component of Zhao Yiman’s story. Zhao was not only portrayed as a “faithful soldier,” like her male comrades, but also as a devoted mother. To the left of the bust was a blown-up photo of Zhao holding her small son, Ning’er, on her lap. The exhibit made it clear that her final thoughts before her execution were of her son. However, this maternal love did not exist in isolation, but was inextricably linked to Zhao’s sacrificial devotion to her country. The purposeful juxtaposition of black and white in the exhibit, used to evoke the landscape of the Northeast, further links Zhao’s affection for her son to that of the land itself and the patriotic rallying cry “huan wo he shan” (return our rivers and mountains).

Even in the 21st century, then, it is clear that there remain important gendered differences between the idealization of the male and female revolutionary martyr. As Xi Jinping has headed a resurgence of the Mao era “cult of the red martyr,” this is particularly worth noting. It is not enough for Zhao to just be an uncompromising revolutionary who sacrificed herself for her country; her motherly affection must be portrayed in conjunction with this, and devotion to family inextricably linked to her devotion to the motherland. Zhao’s patriotism, in this sense, is portrayed as a natural extension of her maternal love, a core component of her femininity.

Even in the 21st century, then, it is clear that there remain important gendered differences between the idealization of the male and female revolutionary martyr. As Xi Jinping has headed a resurgence of the Mao era “cult of the red martyr,” this is particularly worth noting. It is not enough for Zhao to just be an uncompromising revolutionary who sacrificed herself for her country; her motherly affection must be portrayed in conjunction with this, and devotion to family inextricably linked to her devotion to the motherland. Zhao’s patriotism, in this sense, is portrayed as a natural extension of her maternal love, a core component of her femininity.

About the author

Emily Matson is a PhD candidate at the University of Virginia, studying modern Chinese history. Matson’s dissertation is on museums in Northeastern China that commemorate the Manchukuo era and how this regional narrative has interacted with the national narrative from Beijing over time. In addition to modern Chinese history, she also has expertise in modern Japanese history and the interdisciplinary field of historical memory.

Emily Matson is a PhD candidate at the University of Virginia, studying modern Chinese history. Matson’s dissertation is on museums in Northeastern China that commemorate the Manchukuo era and how this regional narrative has interacted with the national narrative from Beijing over time. In addition to modern Chinese history, she also has expertise in modern Japanese history and the interdisciplinary field of historical memory.