BY MIRANDA JARRETT

Early on in my Chinese language studies a decade ago, I struggled to get a clear answer from my teachers on the most accurate way to state my parents’ professions in mandarin. My dad’s job as a psychiatrist was tricky since the one term I could find, jingshenbing yisheng, sounded a bit awkward and generally received amused reactions. My mum’s profession as a marriage and relationship psychotherapist was even trickier – apparently, her profession didn’t even exist in China. I have since learned that therapists and psychological counsellors absolutely do exist in China – and, as anthropologist Li Zhang seeks to explore in her book “Anxious China: Inner Revolution and Politics of Psychotherapy,” they are on the rise.

According to China’s 2022 National Health Insight Report, 91 per cent of respondents claimed to have some kind of psychological problem, which were self-diagnosed in the majority of cases. Young Chinese people face an increasingly competitive school system and job market, leading to the phenomenon of widespread ‘empty-heart disease,’ or kongxinbing in Mandarin. As the anthropologist Yan Yunxiang has shown in his research, the decline in collective values and rise in profit-seeking behaviour have led to a perceived moral crisis, which in turn have instilled a generalized sense of anxiety and distrust. Zhang’s previous work has focussed on the middle class in China, and early on in “Anxious China” she notes that for many material wealth has inspired the questioning of life’s purpose and the deeper meaning of happiness.

It is amidst these various struggles that people are turning in growing numbers towards therapy and self-help, leading to a ten-fold increase in the number of psychological counseling institutions from 2011 to 2020. Moving beyond the medical field, Zhang focuses her attention on the general sense of emptiness, restlessness, and fear described by the people she encounters, which she argues is a defining condition of modern life in China.

During over ten years of anthropological research in Kunming, the capital of China’s southern Yunnan province, Zhang observed countless private therapy sessions and participated in an array of educational workshops on the theme of psychology and mental wellbeing. Bringing her insights together, “Anxious China” sheds light on how practitioners, students, and clients of psychotherapy make sense of their emotional landscapes and seek to improve them in unique ways.

Zhang is keen to emphasize that the surge of interest in psychological theories and therapeutic practices – also called the “psycho-boom” or “psy fever” – is not merely an importation of Western ideas. Here, the Chinese term for localisation – bentuhua (literally meaning “native soil-izing”) – comes in handy. Zhang frequently uses this term to underscore that the process of making traditional Western psy concepts meaningful in Chinese contexts is itself a process of formation and growth.

Whilst Western psychoanalysis heavily informs psychotherapy in China, practitioners select the elements they find to be most effective in their own practices whilst also freely incorporating aspects of Buddhism and Confucianism, as well as lesser known Western therapeutic styles, such as Satir family therapy and positive psychology. Zhang’s key point here is that the evolution of therapy in China is not simply a faddish latching onto old theories by a new demographic, or the blanket application of doctrine. It is an ongoing negotiation of knowledge and instinct, in which practitioners and clients mold diverse and individualized therapeutic practices on the job.

Zhang’s detailed accounts of individual therapists and clients bring to life the human creativity and hope at the centre of this cultivation process. One particularly striking example is the vignette of a therapist who works with one of his clients almost entirely through exchanging pieces of poetry they have written. Through this unique therapeutic dynamic, the client finds a deep forgiveness for her absentee father. These accounts offer a new perspective on therapy everywhere, not just in China.

My own understanding of therapy and mental health has been deeply informed by my parents’ professions. When reading “Anxious China” I realized how tethered I am to specific notions of what constitutes “proper therapy,” which are firmly rooted in psychotherapy’s Freudian origins. Zhang’s account liberated me from this rigid view, inspiring me to see psychotherapy as something that comes in many different forms. It used to be for me a way of mapping the roots of one’s emotional problems. Now, I see this as one powerful and essential component of a larger process – one that is also about learning how to accept ourselves and find joy in life in whatever ways are most meaningful to us.

Zhang herself is a native of Kunming and feels keenly the tragedy of a life left emotionally unexamined. The book is dedicated to her mother, whose death is explored early on in the text, along with Zhang’s depression over her passing. Zhang’s mother suffered from several psychological problems throughout her life, but grew up without the language or freedom to process them. Through her encounters with the emerging psychotherapy world in China, Zhang embarks upon her own healing journey, one that is intertwined with generational trauma.

It is this sensitivity to the pain of others that makes this book so remarkable – each ethnographic account thrums with the empathy the author extends towards her interlocutors. Through weaving together analysis and stories, Zhang creates a deeply personal account of the quest for happiness and fulfillment in an uncertain and fast-changing world.

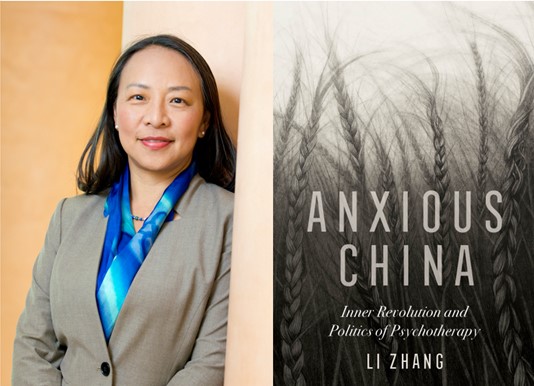

About Li Zhang

Li Zhang (Ph.D. Cornell 1998) is Professor of Anthropology at the University of California-Davis. She is the author of three award-winning books: Strangers in the City (Stanford 2001), In Search of Paradise (Cornell 2010), and Anxious China: Inner Revolution and Politics of Psychotherapy (UC 2020). She is also a co-editor of Privatizing China, Socialism from Afar (Cornell 2008) and Can Science and Technology Save China? (Cornell 2020). Broadly speaking, her research concerns social, political, spatial and psychological repercussions of the market reform and socialist transformations in contemporary China. She was a 2008 John Simon Guggenheim Fellow and the President of the Society of East Asian Anthropology (2013-15). She also served as Interim Dean of the Division of Social Sciences (2015-17) and Chair of Anthropology Department (2011-15) at UC Davis.

About the contributor

Miranda Jarrett is an aspiring China watcher and translator based in London. She recently completed a master’s degree in Chinese Studies at SOAS University of London. Her thesis explored how entertainment television contributes to the phenomenon of ‘therapeutic governance’ in China, which Zhang discusses in her book. Follow her on Linkedin.