BY ANNABELLE JARRETT

It doesn’t matter if our wishes sink…

Shen Yu’s debut feature The Old Town Girls is a dark and dramatic story that highlights the frailty of youth and the struggles borne out of China’s rapid economic development. Part neo-noir crime thriller, coming-of-age story and social commentary, the film offers a warning to viewers on the importance of providing support and strong role models to young people.

WATCH THE FILM HERE. *Note: Spoilers ahead*

Inspired by real events, The Old Town Girls tells the story of Shui Qing (played by Li Gengxi), a teenage girl in her final years of high school. Shui Qing lives with her father and stepmother (her biological mother left shortly after her birth, and her stepmother has not accepted her as part of the family). In one of the first scenes, we see Shui Qing being asked to wait outside while her stepmother’s parents are visiting so that they can have “family dinner.”

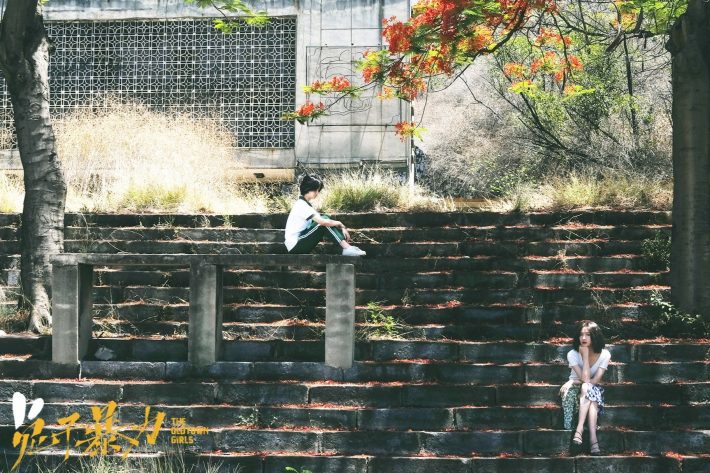

Shui Qing is accompanied by her school friends, Jin Xi (played by Ye Chai) and Yueyue (played by Zhou Ziyue), who both have trouble with their families. In one dramatic scene, Jin Xi – who craves the attention of her wealthy but often absent parents – cries and self-harms while on the phone with them. The absence of Jin Xi’s parents speaks to a social issue in China: the problem of child neglect in families where parents choose to live away from their children in order to work. In making the difficult decision to sacrifice proximity for material support, Jin Xie and her parents have been made casualties of China’s rapid economic development.

A similar phenomenon can be seen through the case of China’s “left behind children” (留守儿童 liushou ertong). “Left behind children” are the children of migrant workers (民工 mingong), who travel from China’s rural regions to work in urban areas. Known as the “floating population”, they are often unable to take their children with them due to government restrictions. Migrant workers make up an estimated 292 million people, according to 2021 statistics.

Jin Xi is juxtaposed with her classmate Yueyue, who is raised by her father Old Ma (played by Pan Binlong), a factory worker and single father. Tensions rise when Old Ma’s boss at the factory, a man with considerable wealth, offers to adopt Yueyue, and give her a life that Old Ma would never be able to. Old Ma, and by extension the viewer, are faced with a moral dilemma: should he accept his boss’s offer in order to give Yueyue all the opportunities he never had, at the cost of maintaining their family?

By focusing on the home lives of these three young women, Shen Yu explores the influence of parenting on a child’s upbringing and the decisions they make. This warning is repeated bluntly at the end of the film, where the text reads:

The purpose of this film is to warn society and families to give more warmth and care to young people during their growth.

Family dynamics drive the plot of the film. One day, Shui Qing’s biological mother, Qu Ting (played by Wan Qian), suddenly returns to town. Her arrival is glamorous; touting big sunglasses with red lipstick and high heels, she tours Shui Qing around in a flashy yellow sportscar. Shui Qing also learns more about why her mother left: she had dreams to become a dancer that could only be realised if she left motherhood and their small city behind to move to Shenzhen.

The film’s brightest moments include scenes when the mother-daughter pair become reacquainted. At one point, Qu Ting arrives at her daughter’s school to teach dance to her class. We see Shui Qing watch on with pride as her classmates follow her mother’s instruction with rapt attention. Another bright moment comes when Qu Ting spends that evening with Shui Qing, Jinxi and Yueyue. The four drive around in the yellow car, laughing and singing along to a ballad. They end the night in a disused tunnel, confessing secrets to one another.

However, as the pair become closer, lurking underneath Qu Ting’s luxurious lifestyle is the truth: she is caught up in organised crime and owes money to a group of gangsters, who demand she pay back money she has borrowed within three days. Shen Yu delivers another warning here: wealth and glamour, though attractive, often come at a price.

Shui Qing becomes fiercely protective of her mother when she is made aware of this threat. She comes up with a plan to kidnap her friend and hold her for ransom, which her mother reluctantly goes along with. Shen Yu opens the film in the middle of the kidnapping plot, which immediately injects the film with excitement and a looming sense of dread as we see how the plan has gone awry.

The film’s descent into tragedy is closely tied up in the fraught family dynamics that are shown. In an email interview with NüVoices, Shen Lu said: “Intentionally or unintentionally, filmmakers create works with marks left by the times they live in. I want to make films that focus more on individuals’ choices, emotions, and the atmosphere of their conditions. Such abstract experience can’t be delivered through texts or other forms of art.”

Before her debut, Shen Yu studied film and explored various mediums including painting, production design and writing. “No other job would allow me to express myself so freely through rigorous work,” she said, adding that she was also inspired to enter filmmaking by her grandfather’s passion for photography. “Some moments he captured revealed the interesting overlap between real life and fictional worlds. Film is the art form of our times.”

The film’s neo-noir elements are reminiscent of Shen Yu’s contemporary Diao Yi’nan, whose 2019 film The Wild Goose Lake also stars Wan Qian. Both films use gritty crime plots and high-contrast lighting with rain at dramatic moments in the plot – all traditional neo-noir elements. Shen Yu cites other crime films – Sergio Leone’s Once Upon a Time in America and Guy Ritchie’s Lock, Stock and Two Smoking Barrels – as filmmaking inspirations.

Unlike much of conventional neo-noir however, The Old Town Girls is a female-centric, female-driven film. The choice is a conscious one as women continue to be underrepresented behind the camera. natural competitive advantages. “Film direction tests one’s artistic instincts and logical judgments,” Shen Yu said. “Women have to go through a unique set of obstacles to get job opportunities…it probably won’t improve significantly in decades. No need to let it get under your skin. Just do what you want to do.”

The film’s setting in a smaller industrial city in southwest China leaves a deep impression. After the dramatic opening scenes of the kidnapping attempt, the opening credits roll. The camera pans across a wide river running between green hills covered in grey, concrete factories. Smoke billows out from smokestacks, rust-coloured metal catches the eye, and tall concrete beams cut across the frame.

When asked what inspired her to tell this true crime story, Shen Yu pointed to the current relentless cycle of tragic news, both in China and the rest of the world. “We all don’t get to live in a bubble” she said. “What saddens and provokes me most are the incidents in which the powerless are pressured to use violence. I want to explore what circumstances brought out the worst in them, and how it snowballed to harm others. Were there possibilities at any point to prevent the tragedies?”

Shen Yu says she rewrote the script once the shooting location was decided, and picked green and yellow as key colours to illustrate the film. Green represents the vegetation of the surroundings and yellow represents sunlight. These colours are also used to evoke the emotions that run through the two main characters. “Yellow represents the mother’s warmth and danger, whereas green represents the daughter’s innocence,” Shen Yu added. The colour yellow also has a pornographic connotation in China, and is used to hint at the mother’s “unsavoury” relationships in the drama.

At the start of the film, Shui Qing and her friends stand atop a bridge, sending a white lantern into the wind as a symbol of hope and good fortune. The lantern catches the air before descending towards the river. They discuss the virtues of making a wish if the lantern sinks into the river, but are quickly chased off the bridge by a security guard from a nearby factory.

In the film’s final moments, Shui Qing is in the passenger seat of the yellow sportscar as it drives past the city and through the bridge out of town. Bathed in warm light, a smiling Shui Qing looks back at the camera. A hopeful tone, perhaps – or a tragic depiction of what could have been, if only the situation had been different. These two scenes underpin the tone of the film: the hopefulness of youth as it meets the challenges and dismays of growing up.

About Shen Yu

Shen Yu has studied painting since childhood and once won “New Concept Composi-tion Contest” for a short novel she wrote. In college, she was drummer in a studentband. From working in the art department of feature film “Beijing Rocks”, she developedthe aspiration to become a film director. She graduated with a MFA degree from the di-recting department of Beijing Film Academy in 2016. She has been involved in makingcommercials, documentaries and films since. She was one of the five finalist of the firstCFDG Young Director Support Program organized by China Film Directors’ Guild.

About the author

Annabelle is a contributing writer at NüStories. She is based in Melbourne, Australia and writes non fiction on cultural subjects including contemporary China and gender politics. Follow her Substack here.