In 2020, as the world grappled with the unprecedented challenges of COVID-19, Hong Kong’s strict pandemic measures stood out as a unique battle against the virus. With stringent regulations and prolonged periods of quarantine, the city’s residents endured an extended period of uncertainty and isolation. While Hong Kong has since cautiously emerged from the pandemic’s grip, Covid-19’s psychological toll on Hongkongers remains palpable.

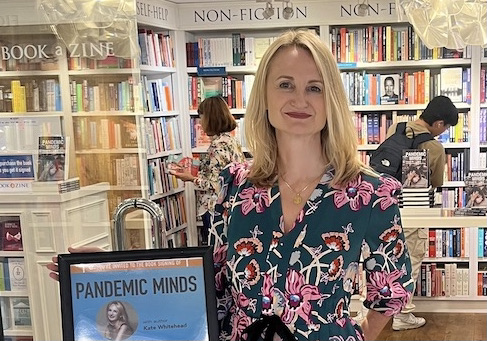

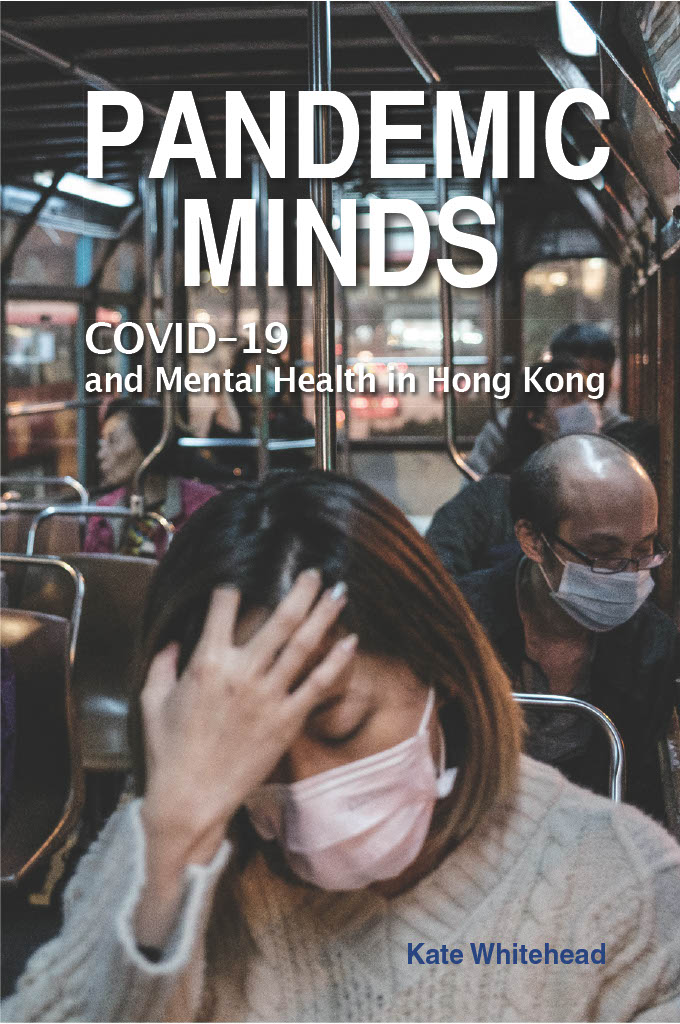

In her latest book, Pandemic Minds: Covid-19 and Mental Health in Hong Kong, journalist and psychotherapist Kate Whitehead uncovers the untold stories of Hongkongers from diverse backgrounds who weathered the storm of the pandemic within the city’s confines. Drawing on 40 in-depth interviews, Whitehead sheds light on the emotional rollercoaster ride that defined life under Hong Kong’s rigorous pandemic measures. From children grappling with the abrupt shift to online learning to adults navigating the complexities of anxiety and isolation, the book offers a poignant narrative of resilience and adaptation in the face of adversity.

But Pandemic Minds is more than just a chronicle of suffering—it serves as a guide to recovery and healing for a community still grappling with the pandemic’s aftermath. Through practical insights and strategies for mental well-being, Whitehead aims to provide a platform discussing mental health, encouraging readers to confront their trauma and embrace a path toward recovery. As Hong Kong embarks on the journey of rebuilding and renewal, this book emerges as a timely reminder of the importance of addressing mental health challenges with empathy, understanding, and resilience.

Siu-hang (not her real name) was 22 weeks pregnant when she returned to Hong Kong from a business trip in July 2022. Her husband and two and-a-half-year-old daughter were both at home. She tested positive for COVID-19 on her second day in a quarantine hotel. In this exclusive excerpt shared with NüStories, Whitehead interviews Siu-hang:

When they told me I was positive, I didn’t know how to handle the situation because I was pregnant. I thought I should see a doctor, so they sent me to hospital. I got to the hospital at about 6 pm and they put me in an isolation room by myself. It was freezing in there, and I was really uncomfortable and waited a long time to see a doctor. The whole time I was in hospital I felt really anxious; I didn’t know what was happening. When I eventually saw a doctor, in the early hours of the morning, he said, “This is a virus; there’s no medication.”

They said they were sending me to Penny’s Bay. I asked if I could go to a [government quarantine] hotel instead, but they said only women 26 weeks pregnant or more could go to the hotel. At 4 am, I was put in a minivan with other people. It was so late, and I was so tired; it was crazy.

When I arrived at Penny’s Bay, they gave me a WhatsApp number to call if I needed anything and an alarm to activate in case of emergency. Dinner was given at 6 pm and breakfast at 8 am.

On the second day, they forgot to give me dinner. I had gestational diabetes and was really hungry. I messaged the WhatsApp number and spent ages going through a series of automated messages: “Is this your first message? What do you want? Please wait for staff to contact you.” But no staff followed up. I wanted to speak to a human, but it was impossible. I put a sign on my door saying, “Pregnant woman; needs to eat”. I saw a “white soldier” [staff in white hazmat suit] walk past, and I opened the window and shouted out, “I haven’t had dinner.” The white soldier spoke to the robot, but he didn’t get a response either. Everything there was automated. I was feeling really helpless, anxious, and stressed. I kept messaging and getting no reply.

By 9 pm, I was starving; I hadn’t eaten since lunch at noon. I saw another white soldier and called out the window again. He said the kitchen was closed, but he could give me instant noodles. I said I was pregnant; I couldn’t eat instant noodles. He said he couldn’t help and walked away. I was angry. I wanted to eat a nutritious meal for my baby. If I could have opened the door, I could have gone to a restaurant, but I was locked up in there. I felt it was now an emergency, so I pressed the alarm. Nothing happened; no one came. The red button was supposed to be the last resort, but it didn’t work. I started thinking if I can’t even get food, what would happen if I had a problem with my pregnancy? What if I started bleeding? I couldn’t sleep and my fears were escalating. I needed to protect my baby.

I called my husband and he found the email for the head of the Centre for Health Protection online. I emailed him at 4 am, telling him, “If I can’t get dinner, which is a small thing, what if I can’t get medical help when I need it?” I made it clear; I’m not pinning the blame on anyone. I want to be collaborative; I just want a solution. I didn’t feel safe at Penny’s Bay. I wanted to be in a place where I could get an ambulance if I needed it. If I’d been able to speak to a human, I don’t think my fears would have escalated like they did.

My email worked, and someone from the Hospital Authority called me at 10 am. I was so grateful that a real person responded and talked to me. I was moved to a quarantine hotel at 6 pm the next day. When I got to the hotel, I realised it was only half full. I don’t know why they hadn’t sent me there in the first place. It took 10 days before I got a negative result and I was released. Normally, I’m very co-operative. I support the Hong Kong government, but could they not take mercy on a pregnant woman? If you can complain in a rational way you can get help, but you have to know how to do it. What about the people who don’t know how to express themselves like that to get their needs met and to be safe? I was very unhappy. Being fed is such a basic need. I appreciate the efficiency of Hong Kong, but everything was very bureaucratic; it lacked the human element.

In the psychology section of the chapter, Whitehead also provides context into Hong Kong’s COVID-19 quarantine measures:

The psychological impact of quarantine can be far-reaching and long-lasting. Research shows that the negative mental health outcomes of quarantine can range from low mood, irritability, exhaustion, and insomnia to confusion, anger, and post-traumatic stress symptoms. And the longer the duration of social isolation, the greater the risk of poorer mental health outcomes, according to a 2021 text co-authored by scholar Samantha Brooks. Hong Kong’s three-week hotel quarantine was one of the longest COVID-19 quarantines in the world.

On February 8, 2020, Hong Kong implemented its first compulsory quarantine for people entering from mainland China. But as the pandemic spread, the policy evolved. Starting from March 19, all travellers arriving from overseas were required to undergo a 14-day compulsory quarantine at home or in other accommodation of their choice. To reduce contact between travellers from overseas and the local community, the government mandated that arrivals from high-risk places must quarantine at hotels, starting on July 25. And in December of that year, the compulsory quarantine was extended to three weeks for almost all international travellers. But as the pandemic began to recede, the policy shifted once again. In early 2022, the quarantine duration was reduced to two weeks and then to one week, the policy finally concluding at the end of September that year.

As social creatures, humans are naturally inclined towards social interaction. But when subjected to social deprivation for 21 days, our inherent nature is put to the test. Research published in 2010 by scholars M.W.M. Wassenberg, D. Severs and M.J.M. Bonten shows that quarantine periods of just one to three days have no negative mental health effects. However, when the isolation period reaches the one-week mark, adverse mental health outcomes begin to appear. A study conducted in the United States in 2003 showed significant negative alterations in mood and anxiety after only one week of isolation. Another study in 2016 by scholars Hyunsuk Jeong, Hyeon Woo Yim, Yeong-Jun Song and others found that people who were isolated for two weeks due to contact with MERS patients suffered from high rates of anxiety and anger, the poor mental health effects persisting even four to six months after their release.

In the wake of Hong Kong’s quarantine, two peer-reviewed studies have delved into its impact on mental health. The first, a qualitative study conducted in 2021 by scholar Judith Blaine, revealed that many individuals who underwent quarantine experienced feelings of isolation, confinement, loneliness, anger, depression, and anxiety.

These individuals reported lingering physical effects such as back problems, muscle aches, and brain fog. However, more commonly reported were lingering feelings of fear, anxiety, anger, exhaustion, lack of energy, and difficulty with social integration. Months after quarantine, some individuals were still experiencing PTSD, depression, and insomnia. Others expressed feelings of anger and resentment towards policymakers for imposing this ‘punishment’ on them. For most participants in the study, it was the lack of openness and transparency that created the adverse psychosocial effects.

In 2022, a study conducted by scholars Hadar Hazan and Christian Chan in Hong Kong examined the mental health outcomes of 248 people undergoing either a two-week or a three-week quarantine. The study found that depressive symptoms peaked in the second week of quarantine. Several predictors of worse mental health outcomes were identified, including poor sleep, a lower sense of meaning, and a longer duration of quarantine.

Interestingly, the study also considered the effect of indirect contact with nature. The results showed that individuals with rooms that had a view of green spaces fared better than those without such a view. The authors suggested that the natural environment may act as a buffer against some of the negative impacts of quarantine. However, the opportunity to select a room overlooking nature was only available to those in hotel quarantine. Furthermore, these rooms were priced at a premium, costing upwards of HK$1,200 per night. As such, this option was only accessible to the wealthy.

Australia adopted a progressive approach to quarantine, screening individuals before they entered quarantine. Those deemed at risk or in need of additional support were assigned to a different type of accommodation, such as a flat with windows that could be opened and from which knives had been removed. Additionally, everyone in quarantine received a daily phone call from the government to check on their well-being and ask how they were coping. In contrast, Hong Kong implemented a one-size-fits-all quarantine policy and no screening to identify individuals who might be vulnerable or at risk. Once the quarantine door was shut, the only person those in isolation saw was a PRC tester, whose job was to quickly and efficiently administer a COVID-19 test. Dressed in full-body biohazard suits, these testers did not inquire about the general well-being of those in quarantine and adhered to a strict and formal script, using only the words necessary to perform their duty: ‘Open the door, sit on the chair, open your mouth.’

These testers could have been empowered to ask individuals how they were doing. This simple act could have provided a means of identifying those who were struggling and allowed mental health professionals to follow up with a phone call and offer psychological support if necessary.

Returning to Hong Kong was an expensive and stressful endeavour due to regular flight cancellations and a shortage of quarantine hotels. However, those who chose to return and undergo quarantine still had the advantage of agency, as they ultimately made the decision to return. In contrast, individuals entering a government isolation facility did not have this choice. People sent to a purpose-built facility, either because they had tested positive for COVID-19 or were a close contact of someone who had, received little prior notice and had no say in where they were sent.

Penny’s Bay Quarantine Centre, located on Lantau Island, was the largest government facility for quarantine in Hong Kong. The sprawling camp opened in July 2020 and accommodated 270,000 people over its two and a half years of operation. Initially, the facility housed close contacts of COVID-19 patients but later transitioned into housing for confirmed COVID-19 cases. In late February 2022, during the peak of the Hong Kong pandemic, Penny’s Bay housed 8,000 people. This period, known as the ‘fifth wave’, marked the camp’s darkest period. As COVID-19 swept across the city, fear of being taken to Penny’s Bay far outstripped concerns over the virus itself. People were terrified of being separated from their families and were often admitted to the camp in a state of high anxiety.

As the number of individuals in the camp swelled, bottlenecks in the testing system emerged. Some individuals who had completed their 21 days of isolation were still waiting for their test results before they could be released. During this period, one man broke quarantine rules and slept outside his isolation unit to protest a lack of support in obtaining urgent medication for a chronic condition. In the midst of this chaos, there were four reported suicide attempts within a 27-hour period, according to Whitehead.

As the pressure reached boiling point, 16 people at the camp staged a walkout due to a lack of clear instructions on when they would be released. A viral video on Facebook showed a visibly distressed woman arguing with security guards. Her clothes and hair were dishevelled, and she shouted, ‘Don’t pretend to care about me! I want to go back! I have recovered! I’m crazy!’ Many people at the camp witnessed the woman’s emotional breakdown, but no one came forward to support her, presumably out of fear of being punished for breaking the rules of their internment. The guards, who might have comforted her, were unable to handle the situation and called the police when she lashed out at one of them.

The climate of fear surrounding the virus and the need to be seen following strict regulations meant that when the police arrived, they failed to recognise that this was a woman in extreme emotional distress. Her case was logged as assault occasioning actual bodily harm. The video is still available on the online platform Reddit. Many of those who commented on the video questioned whether Hong Kong had become tunnel-visioned in its pursuit of protecting people from the virus, losing sight of its humanity in the process.

According to journalist Ethan Paul in 2021, some people have likened Penny’s Bay to a prison, surveillance cameras installed outside every room and reprimands issued from loudspeakers if anyone set foot outside or even opened the door. Common complaints about the camp include the lack of Wi-Fi, poor-quality meals, and unclear information. These are all recognised as critical stressors during quarantine that can have a negative impact mental on health. Research by scholar Samantha Brooks and others has shown that the ability to activate one’s social network and communicate with family and friends is essential in reducing feelings of isolation, distress, and panic. The inability to do so can not only create immediate anxiety but also lead to longer-term distress.’

About Kate Whitehead

Kate Whitehead is an award-winning journalist, psychotherapist, and author based in Hong Kong. She has held positions at South China Morning Post and the Hong Kong Standard, and was the editor of Cathay Pacific’s inflight magazine, Discovery. Her work has appeared in prominent international outlets such as the BBC, CNN, and Forbes. She was a Correspondent Governor on the Board of the Foreign Correspondents’ Club from 2016-2018, continuing to serve on several committees, and is a member of the TRE Board of Directors. Additionally, Whitehead has written two acclaimed non-fiction crime books, After Suzie: Sex in South China and Hong Kong Murders, and has been an advisor to the Hong Kong International Literary Festival since 2016. A recipient of the MIND Media Award in 2019 and 2020, she is a qualified psychotherapist and holds a part-time practice.

Visit her website and buy her book, available on Bookazine, Hong Kong University Press, University of Chicago Press, or Amazon.

About the editor

Daisy Singh Greaves is a British writer and copyeditor for NüStories who also helps coordinate the NüVoices London Chapter. With a keen interest in East Asian politics, gender issues, and the environment, she has written for various media outlets. Currently, Daisy leads communications for a UNESCO-led international environment initiative. Daisy holds a BA in Chinese and English from SOAS, University of London, and an MSc in International Relations from the University of Edinburgh, where she focused her thesis on generational foreign policy attitudes in Taiwan. Whilst studying for a year at Beijing Normal University, she volunteered with the Starfish Project, a charity supporting and rehabilitating trafficked women in East Asia. Since then, she has been passionate about elevating the voices of women and marginalised groups through grassroots journalism and storytelling.